Britain’s decision to leave the EU will have an impact on open data projects and workers, but to what extent is still uncertain

While the post-Brexit mood of Britain has been somewhat dampened by the falling pound and widespread uncertainty as to what the future holds for Britain outside of the EU, the new UK prime minster Theresa May has made one thing clear: “Brexit means Brexit”. The economy is expected to come under pressure, but what does this mean to the UK in terms of open data?

Could Brexit see the UK shelve or at least downsize its commitment to open data as economic uncertainty prompts more public cuts? Or will Brexit actually liberate UK open data and increase transparency, with the Government abandoning austerity in favour of public investment?

It shouldn’t be taken for granted that the Theresa May era will by default embrace David Cameron’s 2010 policy towards open data. The new Prime Minister may have other priorities. The early rush to publish public data sets saw the UK take the global lead in open data – it’s now ranked second behind Taiwan. With data.gov.uk, a single website for UK public data, launching in 2010 and Sir Tim Berners-Lee and Sir Nigel Shadbolt founding the Open Data Institute (ODI) in 2012, the UK was taking positive steps to creating a strong open data culture, but being world champions in this field doesn’t count for much if you can’t back it up with justifiable results.

“The Government has invested a lot of money in open data but then people were asking, ‘what do you do with it?’” says Ian Hetherington, founder and CEO of 3D mapping software company eeGEO. “What’s the visualisation strategy? The data is useless unless you can visualise it.”

Now there are further concerns over the future of the UK’s open data culture. “Cabinet office policy on open data was in the doldrums well before the referendum,” says open data campaigner Owen Boswarva when asked whether he thought Brexit would give the UK’s open data movement a kicking. “Open data is already under threat from austerity, deregulation and cuts to public services.” Brexit, says Boswarva, could make it worse.

“Government could use Brexit as an excuse to stop maintaining datasets that are produced to support EU programmes like Inspire and Eurostat, or to meet EU targets on air pollution and water quality. The UK would also no longer be bound by the PSI Directive, which underpins our regulatory framework for re-use of public sector information,” adds Boswarva.

Chi Onwurah MP, shadow minister for culture and the digital economy, is also concerned.

“Open data is very important to the current and future digital economy and the free flow of data drives innovation and improved services,” she says. “However that free flow of data requires recognised and agreed standards for privacy, security and data formats. Exiting the EU means we may not meet EU standards as a trusted party and there is likely to be less collaboration and research with EU partners. This is likely to stifle innovation unless the government takes action.”

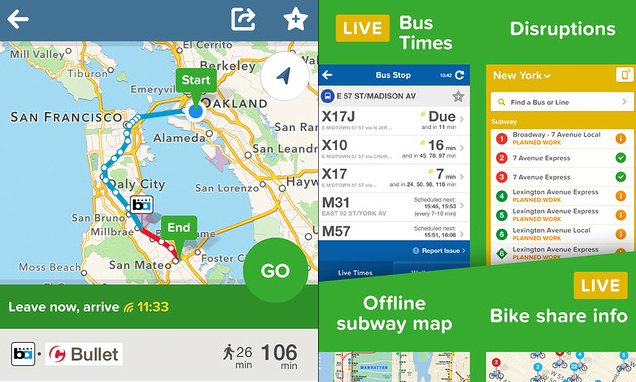

This could have a huge impact as innovation has played a critical role in the unearthing of new open data initiatives, with a number of businesses having emerged over the past couple of years, such as transport app Citymapper, consultancy firm Geolytix, data analysts Spend Network and food marketplace Foodtrade, using public data as an essential base for their core proposition. More established companies such as engineering firm Arup and technical consultancy MIME Consulting use public data too to enhance their services and provide more accuracy to decision making. One start-up to have launched last year with an ambitious plan to “map the world in 3D” was eeGEO. The Dundee-based company uses a number of public data sets with partners to create mapping solutions for governments and businesses but there are concerns, certainly around Brexit and what this may mean in terms of any potential cuts. Open data it seems could be an easy target; and businesses are worried that a more closed, inward looking UK may lose patience with the cost of publishing and maintaining open data sets, vital for their products.

In Europe there is less concern. Marta Nagy-Rothengass, head of unit of the “data value chain” in DG Connect at the European Commission says change is unlikely. The European Data Portal, launched last November shouldn’t be affected, she says. It has over half a million datasets (including 37,000 from the data.gov.uk portal) and geographically is not limited to the EU member states. The UK also signed up to the G8 Open Data Charter in June 2013 committing to transparency and accountability.

But while she talks about the benefits of open data outweighing any initial investment, she wouldn’t be drawn on whether or not the UK would cut back on its open data commitments. So what is the UK mood?

Theresa May has already hinted at her desire for more transparency, at least in business, something which Jeni Tennison, deputy CEO of the ODI, says is a sign that Brexit could in fact be good for open data. She talks about the growing importance of the digital economy to the UK and how, if we are to trade with Europe we will still have to adhere to the same rules and regulations in terms of open data and data protection.

“We will need a strong data infrastructure to underpin our economy,” says Tennison, adding that public and private data will be crucial in enabling digital services.

To a certain extent Boswarva agrees. Brexit, he says, “could be a wake-up call for the UK” if government abandons austerity in favour of public investment.

“Open data is one place to start,” he adds. “It is vital infrastructure for the digital economy. In the post-Brexit environment we will need to be more competitive. Some government departments, most recently Defra, are working hard to sustain that reputation. But many core reference datasets such as addresses and land ownership records remain under lock and key.”

Clearly Brexit will have an impact on open data projects and workers – especially as many are from EU states – but to what extent is still uncertain. However for some including Wendy Carrara, principal consultant at Capgemini Consulting, who was a key member of the European Data Portal project team last year, the idea of cuts is unfeasible.

“We have reached a point of no return,” she says. “Defining barriers or going back in terms of transparency would be very difficult.” In short, it’s just not worth the hassle, something some EU Remain campaigners said just a few long weeks ago.

(This article first appeared on The Guardian)