An ambitious initiative to document agriculture and education is paying off, allowing NGOs and government departments to find data-driven solutions

When the Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, announced that after two years in power his government would embark on a festival of development it was not entirely greeted with warm optimism. During a rally last month at Saharanpur, he spoke about his record in government and approach to social issues.

“We have given importance to building schools, hospitals, roads and transforming the lives of the poor,” he said. “Merely throwing crumbs at farmers is not our way of working. We are trying to solve the problems the farmers face.”

It’s an admirable ambition but as pressure group Wada Na Todo Abhiyan argues in its assessment (pdf) of the last two years of the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance government, talking and delivering are two very different things. “It wouldn’t perhaps be fair to brand Prime Minister Modi’s government as one that talks at the cost of delivering – not yet, that is,” says the report. “However it is now time to ‘walk the talk’.”

The problem Modi has is scale and limited resources. Prukalpa Sankar, co-founder of New Delhi startup SocialCops, believes the solution lies in open data. By using public data to create a realistic picture of social problems, Sankar says resources can be allocated more quickly and effectively.

So how does it work? Sankar cites a project with a large philanthropic foundation in India, which has yet to go public on the project.

“We deployed our platform to help the foundation target over $8m of investments to small and marginal farmers in Bihar, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh,” she says. “Our dashboard assessed each district on nine different layers – crop coverage and productivity, financial services, horticulture coverage and productivity, livestock services and more – relevant to agricultural investment.”

How do NGOs and government departments act on this information?

“The foundation was able to use the dashboard to target its investment based on the change it wanted to drive, from helping farmers access crop insurance in districts with low coverage to empowering female farmers in districts with low female access to financial services.”

It’s not as easy as it sounds. Sankar admits pulling the data together is always a challenge, which is perhaps why no one has done it before.

“Public data is scattered across different websites, in different formats, with different internal file structures and different indicators,” she says. “The biggest challenge encountered in this deployment was to source and structure data from various different formats to bring all the data to one format – and then allow for organisations to query and make decisions from it.”

So what sort of decisions?

“If the goal is to invest in agriculture to impact women farmers, this simple query for ‘Top 50 percentile of female headed rural households’ will allow the foundation to identify focus areas and clusters,” adds Sankar. It’s this sort of drilling down into wide varieties of data that can, says Sankar, help reduce wasted investment and time.

The dashboard, she adds, is to be used by various teams to identify which programmes to invest in and in which geographies investments should be made in order to have maximum impact. It’s the sort of focus that Modi might welcome, as he encourages his ministers to “step out of the comforts of New Delhi” and “hit the road”. This sort of open data analysis would help identify which roads to hit and which problems can be tackled effectively within the budgetary constraints.

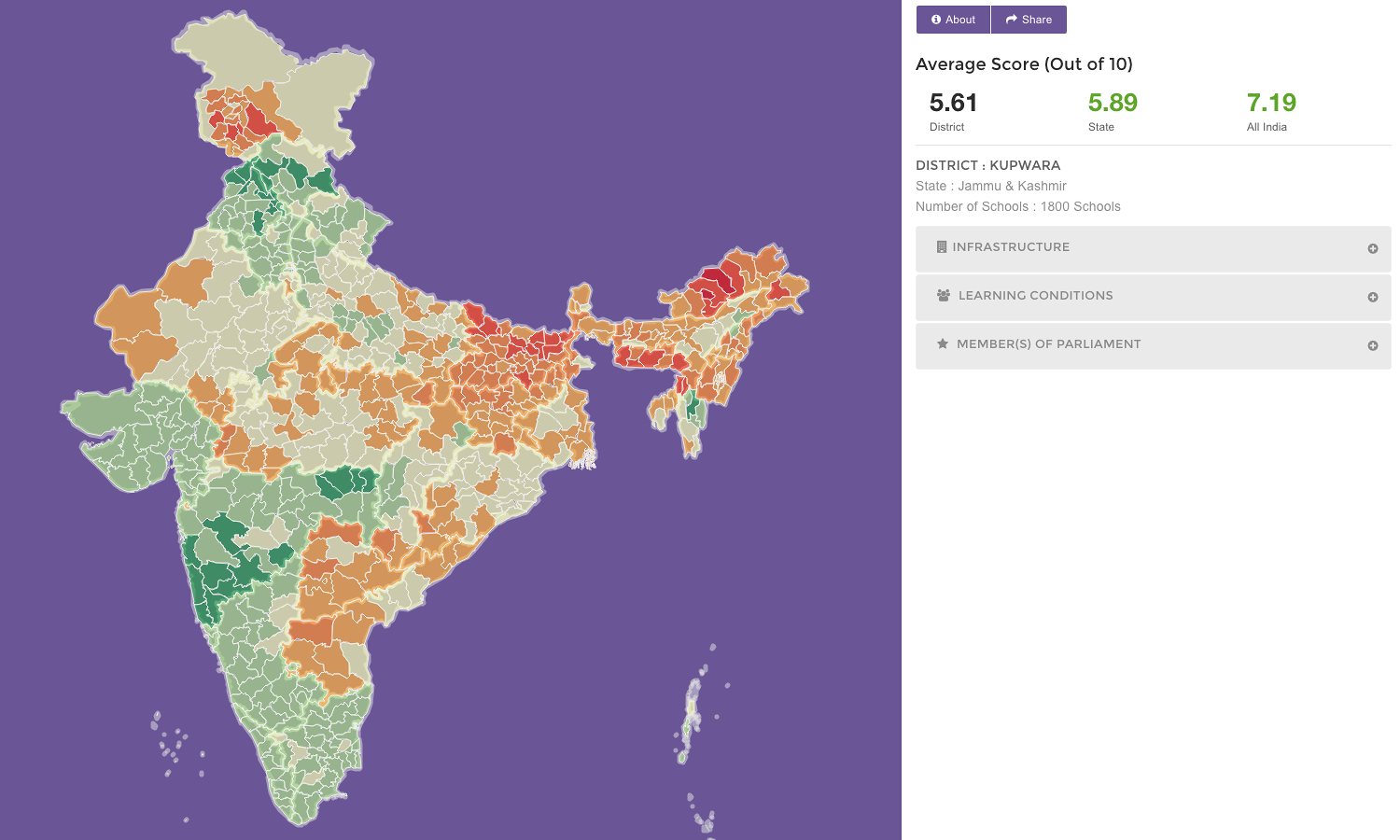

Last year SocialCops mapped the country’s entire education system of 1.4m schools, documenting facilities such as playgrounds, drinking water and toilets for girls, as well as pupil-teacher ratios, student-classroom ratios and teacher-classroom ratios. The country’s 2010 Right to Education Act has already had an impact with 96.7% of all rural children between the ages of 6-14 enrolled in local schools. But Sankar says that due to a shortage of resources, the system suffers from massive gaps including shortage of infrastructure and poor levels of teacher training.

Despite the high overall enrolment rate for primary education, among rural children of age 10, half, says Sankar, could not read at a basic level, over 70% were unable to do division, and half dropped out by the age 14. The resulting map has been taken up by Oxfam India to educate district education officers and members of parliament about what is missing in each district and hopefully drive solutions.

Using open data analysis as ammunition for change will only become more common, says Sankar. But it comes with a warning. While Sankar dismisses the idea that governments may rule too much by data in the future, some are concerned that data-driven government is a threat to civil liberties and politics.

The spectre of algorithmic regulation has been with us for some time, but big data now has the power to make it real. It all comes back to how the data is interpreted and governments won’t always be trusted to make the right call. As such, initiatives like SocialCops will be increasingly key to holding decision makers to account.

(This article first appeared on the Guardian)